Proton Therapy History

Proton therapy is nuclear medicine, meaning it utilizes the characteristics of atoms beneficially. Democritus, an ancient Greek philosopher, first proposed the concept of atoms as an underlying component of matter. However, it was just a concept; he was not a scientist and had no actual physical knowledge of atoms. He gave us the name atom, which means indivisible. In the 20th century, we proved that definition wrong.

Still, "atom" is defined as the smallest possible single unit of an element.

John Dalton, in the 19th century, was the first scientist to propose the existence of atoms, although it was still very basic by current standards. During the 20th century we saw great revelations regarding the structure and potential of atoms, starting with Albert Einstein in 1905.

I received proton therapy in Knoxville, Tennessee, spending two months there on two occasions. I visited the nearby community of Oak Ridge where I encountered the extraordinary history of the Manhattan Project, through which the United States developed an atomic bomb during World War II. That amazing endeavor led directly to the advance of protons.

In the late 1930s, scientists in Germany and elsewhere were investigating the potential of splitting atoms to create an uncontrolled chain reaction which would release an enormous amount of energy, hence an atomic bomb.

Several important scientists who left Germany and Italy and came to the United States made critically important contributions to our war effort.

In 1939, Albert Einstein met with president Roosevelt to describe the threat of Germany developing an atomic bomb. We needed to beat them to it, he argued. After a couple of years of investigation and preparation, things were ready to get off the ground.

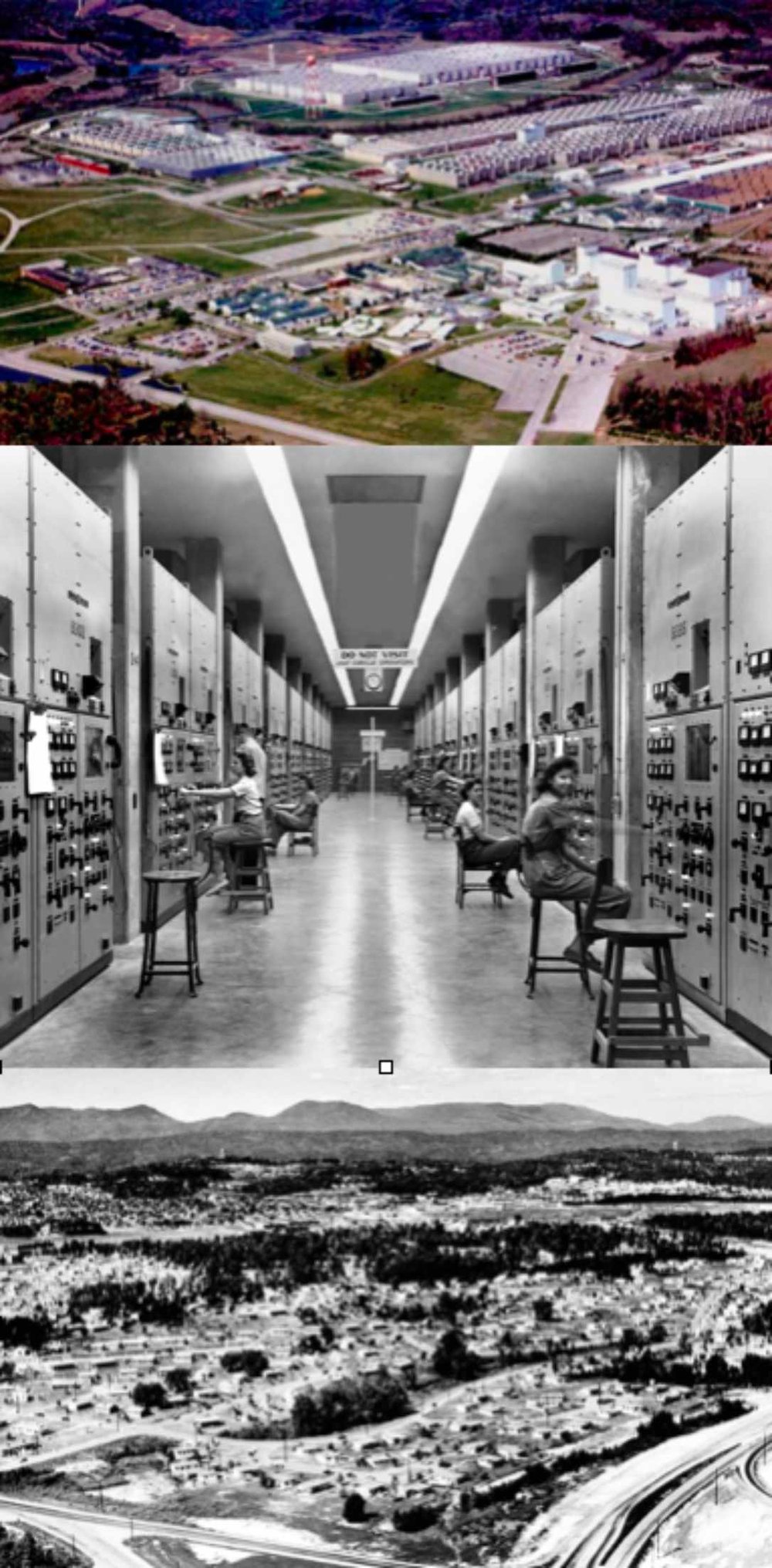

Three main sites were involved, namely, Oak Ridge in Tennessee, Los Alamos in New Mexico, and Hanford in Washington State. Oak Ridge covered 70 square miles yet remained top secret. Its population grew from zero to 70,000 in just a few years. Beside building enormous facilities (one of which was larger than the Pentagon, which had just been finished in Washington DC,) they had to build housing, schools, stores, roads, power stations, and everything else, all as rapidly as possible.

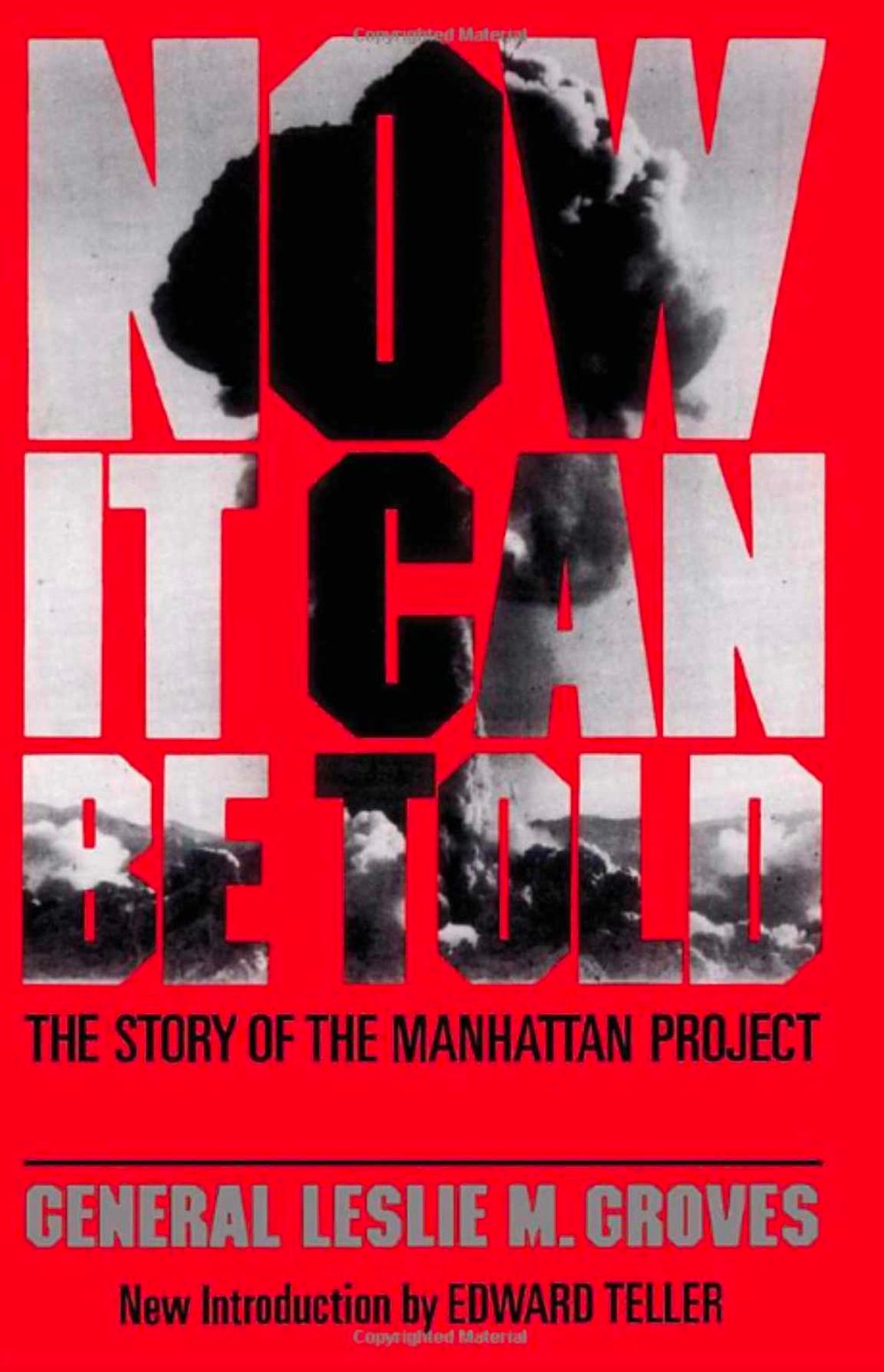

The whole purpose was to separate U-235 uranium isotopes from U-238 as fissionable material for a bomb. The construction was directed by the Army Corps of Engineers. The project was first detailed in their office in Manhattan, in New York City, which gave the name for the whole project. Much of the project remained top secret for decades until finally, in 1983, Gen. Leslie Groves published a detailed book filled with amazing accounts and facts. It is titled: Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. See it on Amazon here: https://www.amazon.com/Now-Can-Told-Manhattan-Roosevelt-ebook/dp/B009SC1LZY. It is well worth a read.

The rapidity of the progress is mind boggling. In 1942 in Chicago, Enrico Fermi created the first chain reaction from fissionable material (plutonium 239). Only then did they discover that it really was possible. Just three years later, on July 16, 1945, we exploded the world’s first atomic bomb in Alamagordo, New Mexico.

The following month, we dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. The degree of destruction and loss of life is regrettable, but the effort to accomplish it is a marvel of brilliance, organization, and determination. Thousands of people did their small part, and a few people played very large parts.

Above top: Buildings at Oak Ridge, built in one year.

Center: Thousands of women watched the gauges of diffusers separating U-235 uranium. They only understood their specific tasks and not the overall purpose.

Bottom photo: Some of the housing at Oak Ridge. Many of those buildings still exist.

If you get caught up in the story of Oak Ridge, here are two more books:

The Girls of Atomic City by Denise Kiernan. https://www.amazon.com/Girls-Atomic-City-Untold-Helped-ebook/dp/B008J4GTU4

City Behind a Fence by Charles W. Johnson (kindle version costs $22, which I think is outrageous, so find it in a library somewhere).

One of the youngest group leaders (in his 20s) working on the Manhattan Project (at Los Alamos) was Robert Rathbun Wilson. He greatly regretted the destruction caused by his efforts. So, in 1946, Wilson published a seminal paper, "Radiological Use of Fast Protons", which founded the medical field of proton therapy. I have read the paper, which is just a few pages long. The key, in my mind, is that he understood so intimately the working of cyclotrons and accelerated charged particles plus the fact that protons can stop at the intended target.

Wilson joined a group of scientists and physicists in developing more powerful particle accelerators for diagnostic and medical purposes. Wilson believed protons could be used to reach previously untreatable tumors deep within the body. He helped design a new powerful cyclotron for Harvard, where he became an associate professor. Thus, for more than four decades, Harvard was the center of proton therapy research.

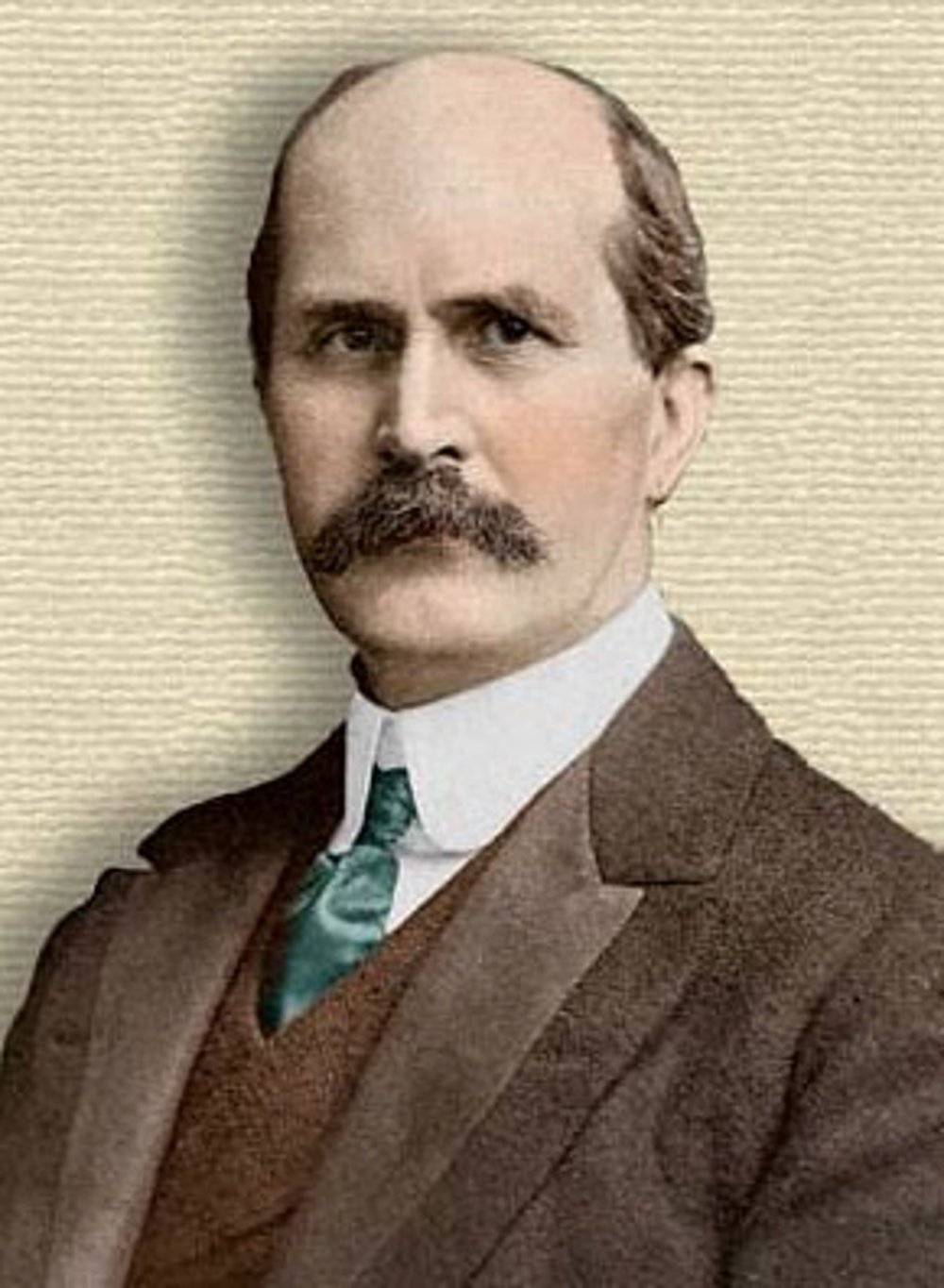

There were precursors to all of this. William Henry Bragg (above), professor of physics and mathematics at Adelaide University in Australia from 1896 to 1909, discovered the phenomenon of protons stopping and giving a burst of energy. When the energy release is graphed, there is a slow incline and then a sudden spike that goes almost straight up. That represents the burst of destructive energy within the tumor. Today that phenomenon is called the Bragg’s Peak, after this gentleman. It is what distinguishes protons from x-rays, which do not (and cannot) stop.

Above: Energy release of protons forming the Bragg’s Peak

The electron was discovered in 1897 by J. J. Thompson, and the proton by Ernest Rutherford (the father of nuclear physics) in 1911. The cyclotron (a type of particle accelerator) was invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley. All of these gentlemen earned Nobel prizes for their ground-breaking work.

The 1930s were a decade of important research and development into the nature and behavior of atoms. Vanderbilt University has detailed much of this history at this website: https://vanderbiltnuclearmedicine.com/era1/early-atomic-discoveries/.

Niels Bohr, a Danish Physicist, was a leading force in Rutherford’s lab at McGill University in Canada. I am reminded of a story of a visitor to Bohr’s office who noticed a horseshoe hung on the wall, with the opening upward. The visitor expressed surprise that as a scientist, Bohr would believe in such an esoteric practice. “You’re right,” Bohr replied. “As a scientist, I find it makes no sense. Fortunately, it works whether you believe in it or not.”

In 1954, the first human was treated with proton beams at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory in California (where the cyclotron had been invented). Eight years later, proton treatments began at the Harvard Cyclotron Laboratory, followed in the mid-1970s by treatments for ocular cancers and larger tumors. It was at Harvard that much of the physics and procedures used for proton therapy were formulated. I find this rather ironic as today one of the harshest critics of proton therapy comes from a doctor long associated with Harvard. Reportedly 9,116 patients were treated at Harvard before the cyclotron was shut down in 2002 and replaced the following year with the current proton center at Massachusetts General Hospital.

From Harvard, Robert Wilson had a stint at Cornell University and then became the director of the new Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory (named after Enrico Fermi), usually called Fermilab, outside of Batavia, Illinois. In the late 1980’s, FermiLab built a synchrotron (an accelerator that works a little differently from a cyclotron) and proton beam transport system for Loma Linda University Medical Center in California which had allotted a million and a half dollars to explore practical uses of proton therapy. That act of vision, in my mind, was the single most important step in the development of proton beam therapy as an accessible cancer treatment. The cost and installation became so high the United States government finally came to the rescue with twenty-five million additional dollars. Today, one of the limiting factors of proton therapy is still the cost of the technology and its utilization.

Dr. James M. Slater, MD, (above) led the effort to establish the proton therapy center at Loma Linda. In 1990, the first patient was treated there at the first hospital-based proton treatment center with equipment powerful enough to penetrate the body and treat cancer. In 1994 the second and third treatment rooms became operational. Loma Linda has now treated more than 30,000 patients. Today, the proton center, now named after Dr. James M. Slater, is headed by his son.

It took thirteen years before the next proton therapy center opened, at Mass General Hospital in 2003 (replacing their old cyclotron). Three years later the third center opened at M D Anderson in Houston, Texas, followed shortly by the fourth at the University of Florida Proton Therapy Institute in Jacksonville, Florida. In 2022, the 40th proton therapy center opened in the United States, with fifteen more under development.

I hope Robert Rathbun Wilson is smiling down from his justified heavenly reward, satisfied with where his efforts have led. Even more exciting is the future. For new developments, see:

FUTURE

*******

HOME PAGE

BACK TO MAIN PROTON THERAPY PAGE

LINKS